The RWKV language model: An RNN with the advantages of a transformer

For a while, I’ve been following and contributing to the RWKV language model, an open source large language model with great potential. As ChatGPT and large language models in general have gotten a lot of attention recently, I think it’s a good time to write about RWKV. In this post, I will try to explain what is so special about RWKV compared to most language models (transformers). The other RWKV post is more technical, showing in detail how RWKV actually works (with a ~100 line minimal implementation).

At a high level, the RWKV model is a clever RNN architecture that enables it to be trained like a transformer. So to explain RWKV, I need to explain RNNs and transformers first.

RNNs

Classically, the neural networks used for sequence (such as text) processing were RNNs (like LSTMs). RNNs take two inputs: a state vector and a token1. It goes through the input sequence one token at a time, each token updating the state. We may for example use an RNN to process a text into a single state vector. This can then be used to classify the text into “positive” or “negative”. Or we may use the final state to predict the next token, which is how RNNs are used to generate text.

Transformers

Because of the sequential nature of RNNs, they are hard to massively parallelize across many GPUs. This motivated using an “attention” mechanism instead of sequential processing, resulting in an architecture called a transformer. A transformer processes all tokens at the same time, comparing each token to all previous tokens in parallel. Specifically, the attention calculates “key”, “value” and “query” vectors for each token, then contributions between all pairs of tokens are computed using those.

In addition to being able to speed up training through massive parallelization, large transformers generally score better than RNNs on benchmarks.

However, the attention mechanism scales quadratically with the length of the sequence to be processed. This effectively limits the model’s input size (or “context length”). Additionally, because of the attention mechanism, when generating text, we need to keep attention vectors for all previous tokens in memory. This requires much more memory than an RNN which only stores a single state.

RWKV

RWKV combines the best features of RNNs and transformers. During training, we use the transformer type formulation of the architecture, which allows massive parallelization (with a sort of attention which scales linearly with the number of tokens). For inference, we use an equivalent formulation which works like an RNN with a state. This allows us to get the best of both worlds.

So we basically have a model which trains like a transformer, except that long context length is not expensive. And during inference, we need substantially less memory and can implicitly handle “infinite” context length (though in practice, the model might have a hard time generalizing to much longer context lengths than it saw during training).

OK, but what about the performance? Since RWKV an RNN, it is natural to think that it can’t perform as well as a transformer on benchmarks. Also, this just sounds like linear attention. None of the many previous linear time attention transformer architectures (like “Linformer”, “Nystromformer”, “Longformer”, “Performer”) seemed to take off.

Benchmarks

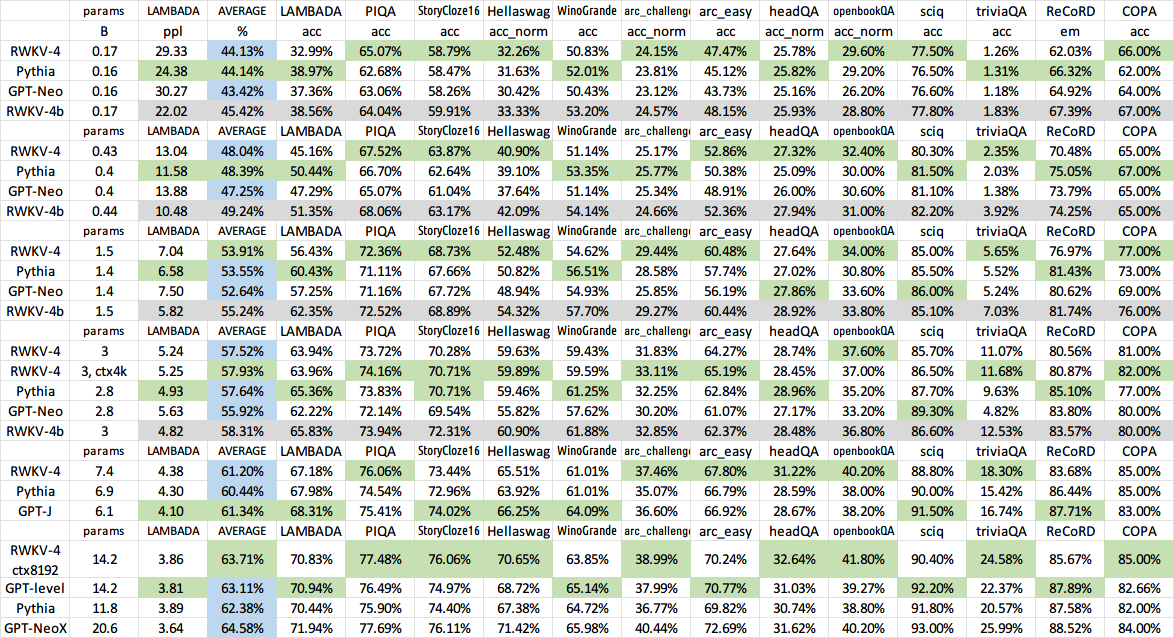

Well, RWKV seems to scale as well as SOTA transformers. At least up to 14 billion parameters.

Contribute

RWKV is an open source community project. Join the Discord and contribute (or ask questions or whatever).

Cost estimates for Large Language Models

When looking at RWKV 14B (14 billion parameters), it is easy to ask what happens when we scale to 175B like GPT-3. However, training a 175B model is expensive. Calculating the approximate training cost of a transformer-like architecture is actually straightforward.

The bottleneck for training is essentially multiplying by all the parameters, and then adding that together, for each input token. With automatic differentiation, we can calculate the gradient with about another 2x that, for a total of 6 FLOPs per parameter per token. So a 14B model trained on 300 billion tokens takes about \(14B \times 300B \times 6 = 2.5 \times 10^{22}\) FLOPs. We use A100 GPUs for training. Using 16-bit floating point numbers, an A100 can theoretically do up to 312 TFLOPS, or about \(1.1\times 10^{18}\) FLOPs per hour. So we theoretically need at least 22 436 hours of A100 time to train. In practice, RWKV 14B was trained on 64 A100s in parallel, sacrificing a bit of performance for various reasons. RWKV 14B took about 3 months \(\approx 140\ 160\) A100 hours to train, thus achieving about 20% theoretical efficiency (since it took about 5x longer than the theoretical minimum). Recent versions can train RWKV 14B at around 50% theoretical efficency.

As a rough price estimate, at the time of writing, the cheapest A100 cost at cloud-gpus.com was $0.79/h. Training the original 14B RWKV there would hence cost around $100k, but with the recent training code improvements we could reduce this to $40k. In practice, there are other considerations like ease of use, timeouts, multi-gpu communication speed, etc. Thus, one might want more high-end options like AWS at $4.096/h. RWKV was trained on compute donated by Stability and EleutherAI.

Now you can imagine that training 10x more parameters and 10x more data will cost 100x more, making it prohibitively expensive.

Footnote

-

Before using a language model on a text, we tokenize the text into tokens. Intuitively speaking, a token is basically a word. In practice, a tokenizer might split words into multiple tokens, has to handle special characters and punctuation, and employ some tricks like adding a token for “end of text”. The 14B RWKV model uses 50277 different tokens. ↩

If you are interested in this kind of research, I would be happy to talk on Discord, email (johanswi@uio.no), or in the comments below.